I've been home now for two weeks, and what with one thing and another have not had the opportunity to finish blogging on my trip. So here goes.

The day before I left from Toulouse, Tony and I spent the day there. Besides being a charming town, there are two major churches there. The earlier is the Cathedral, dedicated to St. Sernin, a magnificent Romanesque building built between 1080 and 1120. The later is the Dominican basilica of the Jacobins, Gothic, 13th and 14th century, where the bones of Thomas Aquinas are now honored under the modern altar. Toulouse was the historic center of the Dominican Order for centuries. The Jacobins is unique, as far as I know, among major basilicas, in that massive pillars march down the center, making any unobstructed view of a high altar (which it lacks) impossible.

I spent the final weekend of my vacation in Oxford with a friend and Associate of the Order, Bob Jeffery. Bob has had a distinguished career in the Church of England, beginning as a curate in the North of England, then working in the C of E central offices in Westminster, then secretary of the British Council of Churches, Dean of Worcester and Sub-Dean of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford. There were other jobs along the way, including Vicar of Headington, near Oxford. Bob also writes C of E obituaries for the Times of London.

He also knows just about everyone. So in September when he mentioned his good friend Henry Mayr-Harting, I could not contain myself, and somehow a dinner party was contrived with the M-H's. What a joy it was! Mayr-Harting is one of the greatest living scholars of ecclesiastical history, and held the Regius Professorship, being the first Roman Catholic to do so. Along with the professorship come duties as a Canon of Christ Church Cathedral, so Bob had the happy task of teaching this ecclesiastical scholar how to be an Anglican cathedral canon, which the Professor vastly enjoyed. He and his wife Caroline are utterly charming.

My good friend Robbin Clark has landed in Gloucester as the Dean of Women Clergy for that diocese, after retiring from a very successful tenure as Rector of St. Mark's, Berkeley. Robbin had been an exchange student from CDSP to Cuddesdon College, a seminary near Oxford, back in the 70's, and I think it is fair to say that it changed her life. She cultivated her relationships in the C of E for many years, and at a reunion a few years ago at Cuddesdon, where she was honored as their first woman seminarian, she let it be known she would be open to an interesting ministerial challenge upon retirement, and lo and behold! Robbin came over Saturday for lunch and met Bob, and then she drove me out to Cuddesdon, which I had never seen. Such a beautiful place! And the seminary is apparently doing well on all fronts. Deo gratias.

On Sunday, Dec. 11, I went with Bob to St. Peter's, Wolvercote, a short distance outside Oxford, where he presided and preached. The place was full, a wide range of ages, full bench of acolytes, and the six bells were pealed by an expert team for half an hour or so before the service. Of course, the Anglican world being approximately two inches wide, there was someone there I knew: Joanna Coney, who is now the head of Franciscan Tertiaries in Europe, and who had been at West Park in September for the international Anglican Franciscan leadership conference. A joyous reunion. And a joyous morning!

In the afternoon we went to the Ashmolean Museum, completely reworked, with a beautiful atrium and staircase. I am afraid, however, that the museum has chosen the route of educational and informative display, so that there are relatively few objects on view and a plethora of large, explanatory posters to tell you all about them. I would rather see more objects, but I suppose even Oxford needs to cater to the uninformed. My old friend the Alfred Jewel was there, however, so I was consoled.

We had tea and Vespers at the All Saints convent. They are few -- nine, I think, with seven in attendance at Vespers -- but very warm and welcoming. I cannot think of a nicer way to end the weekend and my vacation.

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

Monday, December 5, 2011

Avignon, Nîmes and Preaching in Limoux

I am now in the final week of my stay in Alet-les-Bains with my good friend Tony Jewiss. We had a wonderful short trip last week to Avignon and to Nîmes. There are three outstanding reasons to visit these places, apart from their own civic virtues: the Papal Palace in Avignon and the Arena and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes.

It is hard, I suppose, for any medievalist to visit the Papal Palace in Avignon and not have a world of reactions. The French papacy of the 14th Century and then the papal schism (1378-1417) were a huge part of the religious background to the age of Chaucer, Piers Plowman, and early English mystical writings like The Cloud of Unknowing, to say nothing of the vast Christian culture beyond England. So as Tony and I wandered around the vast palace, I had a wonderful meditation on the place of renewed Church administration in Christian culture (the Avignon popes modernized, in their own terms, the administration of the Church) and on the role of Church patronage of the arts.

The Arena and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes are among the best preserved ancient Roman buildings anywhere, both being the most perfect examples of their type that exist in Europe. The Arena is a medium-sized amphitheater for gladiatorial shows and other blood sports. It was used for other purposes through the centuries and its restoration first undertaken by Napoleon. It is still used for concerts, operas, and even for skating in the wintertime. The Maison Carrée is a temple built to honor the two sons of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, whom the Emperor Augustus, Agrippa's best friend, had adopted as his own. Exquisite!

Tony invited me to preach twice while I was in Limoux. The first was on Christ the King two weeks ago, and I preached extemporaneously. The second was yesterday, Advent II. I wrote it out early in the week so that it could be sent to the lay readers of the Church of England Chaplaincy in this area -- there are not enough priests to cover all the congregations, and it was Tony's turn to provide the sermon. I found it strange preaching a text that I had written some days ago, and to realize that several others might be preaching it as well. To facilitate others' reading, it was devoid of personal reference, which my sermons generally include. My usual practice is to write sermons the day before I preach them, so they are fresh in my mind in the morning. On Sunday I found myself reconsidering and reframing the material in my mind and then, in delivery, modifying and embellishing and providing background as I went on, which made it longer than I had intended. So here is the original text:

Isaiah 40: 1-11

2 Peter 3: 8-15a

Mark 1: 1-8

“Comfort ye”, in the words of the Authorized Version used by Handel in Messiah: “Comfort ye.” Israel in exile in Babylon has just learned that they are to return to Jerusalem. What they thought impossible is about to happen: the cruel exile, in which they had been ripped from Jerusalem, from Zion, from the City of David and the City of the Temple of the Most High God, is about to end. The magnificent poetry of the prophet of the end of the exile, whom we call Second Isaiah, begins with these words, and unfolds not only the joy of an Israel renewed, but one of the most profound meditations on the nature of God and reality in human thought, and not just in abstract thought: The one who comes with might, whose arm rules for him, is also the one who feeds his flock like a shepherd, who carries the lambs in his bosom and gently leads the mother sheep. What joy to contemplate the hope of return, God’s peace accomplished in the love of the Almighty for his flock.

This return of God’s people from their exile is how Mark begins his Gospel, the image he uses as the beginning of the Good News of Jesus Christ: Prepare the Way of the Lord. John the Baptist is calling Israel out into the wilderness so she can discover what she really is: a people in trouble, a people who need to turn around, which is what repenting is. Leaving behind their sins in the desert and being washed in the Jordan links them not only to the people returning from the Exile, but to the people escaping Egypt, wandering in the wilderness, receiving a new identity, a new life and a new direction at Sinai and at last entering into the Promised Land. John wants a new beginning. He doesn’t know what that beginning will be or who will lead it, or where it will go. His job is to get the people ready, get them to the River. He is the new Moses, waiting for the new Joshua.

When we confront scripture, especially texts as beautiful, multi-layered and moving as the beginnings of Second Isaiah and Mark, there are always several things going on in us at once. One is just to understand the text itself, where it came from, who it was written for and why, and what it meant at the time. Our Bible studies and private reading and continuing studies help us with that. What we learn about the language and history and customs of these times is preparing us for the second step, which is to imagine ourselves back into those days and into the lives of people and what happened to them. What joy must have gripped the Israelites in Babylon, even as they contemplated the hard journey ahead, trusting that steep mountains and deep valleys would be made passable on their journey back to Palestine. And what fearful anticipation must have gripped Israel as the Baptist announced that Something was about to happen, and that there was a way they could be made ready for it. People must have pondered all those things they had done and left undone, and rejoiced that there was a way to deal with them.

But when we have done our work of study, and when we have allowed our study to instruct our imagination, something else also remains. The Scriptures are the Word of God at least in part because they speak to us, to us as we are now. The Scriptures demand our best efforts to understand them as they are as texts and as they were as events, but all that is preparation for the life they give us.

The writer of Second Peter seems to have pondered this double sense of time, time then and time now, the conflation of the ancient time of God’s actions with his people in the past and the urgency of our time in the present. “With the Lord one day is like a thousand years.” The past and the present are one in God’s time. The Lord is not slow, but patient. Nevertheless, the day of the Lord will arrive like a thief in the night. So the time of the past and the time of the future come together in the present, in our lives now. The Babylonian Captivity, the Jerusalem of the unspeakable Herods, the Israel of then, is also ours today.

Who among us has not been in exile, been shut out, been carried away from our true home, whether in physical fact or in the sometimes greater reality of our inner lives, and longed for return? Who among us has not known deep in our hearts that our lives have gone wrong, and longed for the call to the wilderness, where they can be cleansed and made ready for something new? The truth is that the human condition is often to live in an alien land, sometimes objective and real outside ourselves, sometimes deeply interior. The truth is that it is our nature to go astray, at best to wander off into paths that take us nowhere good, or at worst, to take the roads that lead us into deep trouble. There is yearning deep in our hearts for the home we have left. There is a deep need in each of us to find what we have done wrong and right it, so that we can begin to be who we should be. These are Advent yearnings, Advent needs: We want the one to come who will save us, rescue us, and bring us home.

St. Augustine of Hippo was one of the great psychologists and doctors of the human heart. He confronted this longing in his own life and did something about it: he turned from the way of self to the way of God. And along the way he came to a profound understanding of himself, an understanding that can unfold some of the yearning, the desire for change and the conflation of time that these great texts give us. He locates it in our very natures, in the image of God written in our hearts at the moment we came to be, which is so powerful that it animates all our desires: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” Our hearts are restless. We feel we are somehow in the wrong place, even when we are happy. We know our lives need change. And somehow we know that nothing in this world will completely satisfy those needs. It is not where we go or what we do or what we get or what we have that give us the peace and joy we crave. It is the love of God that gives us the hope we need, the hope that He will take us in his arms and tenderly lead us home, that when we meet him in the wilderness we will be made ready for his coming among us.

It is hard, I suppose, for any medievalist to visit the Papal Palace in Avignon and not have a world of reactions. The French papacy of the 14th Century and then the papal schism (1378-1417) were a huge part of the religious background to the age of Chaucer, Piers Plowman, and early English mystical writings like The Cloud of Unknowing, to say nothing of the vast Christian culture beyond England. So as Tony and I wandered around the vast palace, I had a wonderful meditation on the place of renewed Church administration in Christian culture (the Avignon popes modernized, in their own terms, the administration of the Church) and on the role of Church patronage of the arts.

The Arena and the Maison Carrée in Nîmes are among the best preserved ancient Roman buildings anywhere, both being the most perfect examples of their type that exist in Europe. The Arena is a medium-sized amphitheater for gladiatorial shows and other blood sports. It was used for other purposes through the centuries and its restoration first undertaken by Napoleon. It is still used for concerts, operas, and even for skating in the wintertime. The Maison Carrée is a temple built to honor the two sons of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, whom the Emperor Augustus, Agrippa's best friend, had adopted as his own. Exquisite!

Tony invited me to preach twice while I was in Limoux. The first was on Christ the King two weeks ago, and I preached extemporaneously. The second was yesterday, Advent II. I wrote it out early in the week so that it could be sent to the lay readers of the Church of England Chaplaincy in this area -- there are not enough priests to cover all the congregations, and it was Tony's turn to provide the sermon. I found it strange preaching a text that I had written some days ago, and to realize that several others might be preaching it as well. To facilitate others' reading, it was devoid of personal reference, which my sermons generally include. My usual practice is to write sermons the day before I preach them, so they are fresh in my mind in the morning. On Sunday I found myself reconsidering and reframing the material in my mind and then, in delivery, modifying and embellishing and providing background as I went on, which made it longer than I had intended. So here is the original text:

Isaiah 40: 1-11

2 Peter 3: 8-15a

Mark 1: 1-8

“Comfort ye”, in the words of the Authorized Version used by Handel in Messiah: “Comfort ye.” Israel in exile in Babylon has just learned that they are to return to Jerusalem. What they thought impossible is about to happen: the cruel exile, in which they had been ripped from Jerusalem, from Zion, from the City of David and the City of the Temple of the Most High God, is about to end. The magnificent poetry of the prophet of the end of the exile, whom we call Second Isaiah, begins with these words, and unfolds not only the joy of an Israel renewed, but one of the most profound meditations on the nature of God and reality in human thought, and not just in abstract thought: The one who comes with might, whose arm rules for him, is also the one who feeds his flock like a shepherd, who carries the lambs in his bosom and gently leads the mother sheep. What joy to contemplate the hope of return, God’s peace accomplished in the love of the Almighty for his flock.

This return of God’s people from their exile is how Mark begins his Gospel, the image he uses as the beginning of the Good News of Jesus Christ: Prepare the Way of the Lord. John the Baptist is calling Israel out into the wilderness so she can discover what she really is: a people in trouble, a people who need to turn around, which is what repenting is. Leaving behind their sins in the desert and being washed in the Jordan links them not only to the people returning from the Exile, but to the people escaping Egypt, wandering in the wilderness, receiving a new identity, a new life and a new direction at Sinai and at last entering into the Promised Land. John wants a new beginning. He doesn’t know what that beginning will be or who will lead it, or where it will go. His job is to get the people ready, get them to the River. He is the new Moses, waiting for the new Joshua.

When we confront scripture, especially texts as beautiful, multi-layered and moving as the beginnings of Second Isaiah and Mark, there are always several things going on in us at once. One is just to understand the text itself, where it came from, who it was written for and why, and what it meant at the time. Our Bible studies and private reading and continuing studies help us with that. What we learn about the language and history and customs of these times is preparing us for the second step, which is to imagine ourselves back into those days and into the lives of people and what happened to them. What joy must have gripped the Israelites in Babylon, even as they contemplated the hard journey ahead, trusting that steep mountains and deep valleys would be made passable on their journey back to Palestine. And what fearful anticipation must have gripped Israel as the Baptist announced that Something was about to happen, and that there was a way they could be made ready for it. People must have pondered all those things they had done and left undone, and rejoiced that there was a way to deal with them.

But when we have done our work of study, and when we have allowed our study to instruct our imagination, something else also remains. The Scriptures are the Word of God at least in part because they speak to us, to us as we are now. The Scriptures demand our best efforts to understand them as they are as texts and as they were as events, but all that is preparation for the life they give us.

The writer of Second Peter seems to have pondered this double sense of time, time then and time now, the conflation of the ancient time of God’s actions with his people in the past and the urgency of our time in the present. “With the Lord one day is like a thousand years.” The past and the present are one in God’s time. The Lord is not slow, but patient. Nevertheless, the day of the Lord will arrive like a thief in the night. So the time of the past and the time of the future come together in the present, in our lives now. The Babylonian Captivity, the Jerusalem of the unspeakable Herods, the Israel of then, is also ours today.

Who among us has not been in exile, been shut out, been carried away from our true home, whether in physical fact or in the sometimes greater reality of our inner lives, and longed for return? Who among us has not known deep in our hearts that our lives have gone wrong, and longed for the call to the wilderness, where they can be cleansed and made ready for something new? The truth is that the human condition is often to live in an alien land, sometimes objective and real outside ourselves, sometimes deeply interior. The truth is that it is our nature to go astray, at best to wander off into paths that take us nowhere good, or at worst, to take the roads that lead us into deep trouble. There is yearning deep in our hearts for the home we have left. There is a deep need in each of us to find what we have done wrong and right it, so that we can begin to be who we should be. These are Advent yearnings, Advent needs: We want the one to come who will save us, rescue us, and bring us home.

St. Augustine of Hippo was one of the great psychologists and doctors of the human heart. He confronted this longing in his own life and did something about it: he turned from the way of self to the way of God. And along the way he came to a profound understanding of himself, an understanding that can unfold some of the yearning, the desire for change and the conflation of time that these great texts give us. He locates it in our very natures, in the image of God written in our hearts at the moment we came to be, which is so powerful that it animates all our desires: “You have made us for yourself, O Lord, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you.” Our hearts are restless. We feel we are somehow in the wrong place, even when we are happy. We know our lives need change. And somehow we know that nothing in this world will completely satisfy those needs. It is not where we go or what we do or what we get or what we have that give us the peace and joy we crave. It is the love of God that gives us the hope we need, the hope that He will take us in his arms and tenderly lead us home, that when we meet him in the wilderness we will be made ready for his coming among us.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Remembrance Day

I am happily into my vacation in Languedoc-Roussillon, having arrived a little fatigued on Friday (American frm JFK to Madrid, long wait at Madrid/Barajas, and then a little less than an hour to Toulouse). My friend Tony Jewiss, with whom I am staying, is the priest for the Anglican congregation in these parts, a delightful group of expatriate British who meet in the old Augustinian convent church in Limoux. I will preach there this coming Sunday. Sunday the 13th was Remembrance Day, which is sort of like Veterans' Day but with a lot more to it. C of E Churches generally make a thing of it, and it's a reminder of how much more closely the C of E represents the official English culture than the Episcopal Church does the American. Morning Prayer with sermon. A turnout of about 35 or so. A good coffee hour (with actual coffee) afterward, and then more than a few repaired to the Limoux town square for an aperatif.

I thought Tony's sermon was quite good, and asked him if I might share it on this blog. So here goes:

Zephaniah 1:7,12-end

1 Thessalonians 5:1-11

Matthew 25:14-30

Psalm 90:1-8

A friend of mine is the organist at West Point Military Academy, not far from the Monastery at West Park where Fr. McCoy lives. The chapel at West Point, coincidentally, has the largest organ in a public worship space in the country.

Meredith plays every Sunday and for many events throughout the year. There, as in most places boasting elite branches of the services, graduation is a spectacular event. Massed marching, bands and plenty of pageantry – not quite as much as you are used to perhaps, but a good attempt to imitate England’s undisputed superiority when it comes to marching about, accompanied by bands, anyway.

Even organ music, as the chapel is used for ceremonial events as well.

Meredith knows hundreds and hundreds of cadets and officers by name. She sees them arrive, all gangly and awkward, from hometown wherever it may be, and sees them whipped into shape, taught to walk ramrod straight, turned out to be officers, then sent off to war.

Not war really. Actually, there are no wars at the moment. War requires formal declaration and that in turn establishes some rules. The many conflicts around the world right now fall into other categories – in the case of the ones we hear about most, Iraq and Afghanistan, these are technically Interventions. There are no rules for Interventions. The War on Terror is just a loose use of words, made all the looser by the absence of a War on Illiteracy, a War on Poverty or a War against human trafficking.

Meredith’s duties at the Military Chapel have another dimension, and it is to play the funerals of some of her cadets who come home in a box. There are usually several every week, and occasionally, several in one day. She says it is rare for her not to be able to recall the name of the young man or woman now being eulogized as a hero,

and then put to rest.

In the western world, these events are solemn and restrained. Grief is controlled, losses borne stoically, and usually with great dignity.

A small town in the UK welcomes each cortege that passes through, bearing the bodies of fallen servicemen and women from their arrival at the nearby air base. It is their ministry, their expression of solidarity and sympathy. It is quiet and very moving.

The last few years have given us very graphic images of how different things are in the Middle East. The loss of an Arab boy or girl results in noisy crowd scenes, women throwing themselves over the open coffin being borne, lurching precariously through the streets. Young men fire rifles into the air, and it is chaos.

Yet mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, wives and children everywhere are equally devastated at their losses. All ask the same question, and it is the very question we must also keep before us as we are gathered here to do honor to, and pay respect to, those who have died in the service of their country.

I do not like the expression – “gave their lives for their country.” That to me implies some kind of intention to go and not return. Armed conflicts have always relied upon that sense of invulnerability that the young enjoy, to send them with a certain eagerness to play a role in the Army or the Navy or the Air Force. I think, and hope, that all of them have every intention of coming home fit and well, appreciated by their country and with a sense of having furthered the cause of peace. But even among the survivors, it is not always that way.

In my last job in New York I was asked to be on the selection committee to choose a national chaplain to oversee the activities of the Church’s corps of service chaplains – several hundred of them stationed all over the world. The candidates were narrowed down to three, and it was a hard choice as they were all very well qualified. Each candidate told us things we did not know. Things that change and expand the ministry of chaplaincy in terms of scope and in terms of longevity. They all spoke of the very substantial percentage of service men and women who came home with devastating injuries. In times past they would have all died, but now modern field medicine saved their lives, but not their limbs.

Thousands of them suffer brain injuries caused by their heads being banged about in those large and instrument-laden helmets – designed as much to provide tactical information and communications, as they are to protect the head.

We don’t think much about this aspect of the lives and work of those who fight for us, even on days such as Remembrance Day, although we should. Nor do we think deeply about who these men and women are. The life in service is not for every one, no, not at all. If it is for the sons and daughters of the rich and famous at all, it is through the portals of officer school and the privileges of rank.

As far as the rank and file in concerned, the Service life is an option when jobs are scarce and one’s social rank prevents a life in banking or commerce or politics.

Here are a few statistics that I think you will find shocking – a recent study shows that almost 60% of veterans suffered physical abuse as children, and almost 40% suffered sexual abuse. In one country, in 2010, the Army reported more deaths by suicide than deaths in the field.

Over 50% suffer some form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and almost all have heightened awareness, and reaction to, excessive light and sound.

Much has been written in recent years about how congregations can help returning service people find peace and reconciliation after their field experiences. I don’t believe we have that opportunity but hundreds of congregations do, and are treating this ministry as vital, learning how to avoid clichés and platitudes and how to gently ease these men and women, injured as much psychologically as physically, back into the mainstream of community life.

Military families need support as well. It is hard to even imagine the pressures placed on a family unit as the returning veteran deals with spouse and children who cannot really conceive of the things he or she has so intimately experienced.

The words from Zephaniah may not resonate easily with us. At first one wonders what has possessed the compilers of the lectionary to choose such a reading for today. But I might speculate that they would resonate clearly with someone whose memories are shot with the terrible possibilities of which Zephaniah speaks.

The uncertainty, the apprehension, the sudden percussion, the falling rubble, the dust, the debris, the shattering noise, the blinding incendiary. Thank God most of us will never know it – but every veteran does.

The words of Paul to the Thessalonians may not resonate immediately with us either, but they are actually words of encouragement.

Certainly Paul employs some military imagery but he is really saying that there is an alternative to conflict. This reading is a kind of mirror image to Zephaniah. It shows that there is another way, another ideal, another possibility. We need to hold these peaceable possibilities in mind even as we remember those who carried those ideals into the field of conflict itself.

Last week the Prime Minister entertained the organization that offers support to veterans, at a party at 10 Downing Street. His remarks, aimed as much at the cameras as at those present, were a study in political opportunism. His speech writer had dredged up every cliché possible. Apart from his probably intimate knowledge of the line item in the national budget, it was pretty obvious that he had no real empathy with the work of rehabilitating veterans.

I wish his speechwriter had instead translated the gospel story we’ve listened to this morning into a more meaningful and more sincere message for the cameras. Even when delivered by well groomed and sleek Prime Ministers, the truth can be convincing.

The resources delegated to the servants in the story were in fact immense. The responsibility therefore delegated to them was immense as well. The talent was a huge amount of money, and the risks involved in investing it were huge as well.

Time is a crucial element in the gospel story as well. Jesus is preparing his hearers for the uncertainty of the time element – they were expecting His return to be immediate but he says that is not to be the case. Instead, that information is hidden, and therefore the need for proper preparation and anticipation.

Next, actually possessing the money in the first place is not evidence that the enterprise will succeed. The talents were bestowed because the owner believed his servants already had ability to succeed. The entrusting of the money did not necessarily carry with it the actual ability to succeed.

Then, there is the element of risk, and as we know, one of the servants did not take any risk. He kept his part of the money secure, but he did not use it to achieve anything. He did not do the work that the other two did. His was a passive engagement with the task; theirs was active.

Lastly, the issues of reward and punishment. There are consequences to every decision, every action, every engagement.

The men and women of the armed services are a priceless resource – they are people, they are real, and their value as children of God is immeasurable.

They are given tasks that do not fall into the ideal definition of life. They must take enormous risks, make value judgments and deploy their resources with boldness and with not much time to ponder decisions. There are not many rules as to who succeeds or fails to succeed – but their trajectory has to be forward. They cannot be idle, like the third servant.

All three servants respond to their own view of the Master – two are inspired to please him and to succeed in the goals he has set. The third does not trust the Master and fears his reaction if he should not succeed. It is as if he said to himself “I knew you were unreasonable, and that there was no way to please you, so I decided not even to try”.

This tells us that both conflict and opportunity must be met by people who may or not be qualified. Trained, yes, but temperamentally qualified, not necessarily.

Either way, what we ask of the women and men of the armed forces is not reasonable, yet we expect it of them anyway.

And therein lies the real reason we gather today. Rising to do the work of war is the response to an unreasonable request – and in some cases, demand. Yet veterans did respond, did grasp the higher vision, and did what we have come to call duty

despite the risks.

We remember the ones who could not return. We care for the ones whose injuries prevent their being able to enjoy a full life. And we nurture back to health the ones whose experiences have wounded them in other ways.

And we commend them to God’s loving and healing care, even as we earnestly continue to pray for the peace that they have tried to attain.

I thought Tony's sermon was quite good, and asked him if I might share it on this blog. So here goes:

Zephaniah 1:7,12-end

1 Thessalonians 5:1-11

Matthew 25:14-30

Psalm 90:1-8

A friend of mine is the organist at West Point Military Academy, not far from the Monastery at West Park where Fr. McCoy lives. The chapel at West Point, coincidentally, has the largest organ in a public worship space in the country.

Meredith plays every Sunday and for many events throughout the year. There, as in most places boasting elite branches of the services, graduation is a spectacular event. Massed marching, bands and plenty of pageantry – not quite as much as you are used to perhaps, but a good attempt to imitate England’s undisputed superiority when it comes to marching about, accompanied by bands, anyway.

Even organ music, as the chapel is used for ceremonial events as well.

Meredith knows hundreds and hundreds of cadets and officers by name. She sees them arrive, all gangly and awkward, from hometown wherever it may be, and sees them whipped into shape, taught to walk ramrod straight, turned out to be officers, then sent off to war.

Not war really. Actually, there are no wars at the moment. War requires formal declaration and that in turn establishes some rules. The many conflicts around the world right now fall into other categories – in the case of the ones we hear about most, Iraq and Afghanistan, these are technically Interventions. There are no rules for Interventions. The War on Terror is just a loose use of words, made all the looser by the absence of a War on Illiteracy, a War on Poverty or a War against human trafficking.

Meredith’s duties at the Military Chapel have another dimension, and it is to play the funerals of some of her cadets who come home in a box. There are usually several every week, and occasionally, several in one day. She says it is rare for her not to be able to recall the name of the young man or woman now being eulogized as a hero,

and then put to rest.

In the western world, these events are solemn and restrained. Grief is controlled, losses borne stoically, and usually with great dignity.

A small town in the UK welcomes each cortege that passes through, bearing the bodies of fallen servicemen and women from their arrival at the nearby air base. It is their ministry, their expression of solidarity and sympathy. It is quiet and very moving.

The last few years have given us very graphic images of how different things are in the Middle East. The loss of an Arab boy or girl results in noisy crowd scenes, women throwing themselves over the open coffin being borne, lurching precariously through the streets. Young men fire rifles into the air, and it is chaos.

Yet mothers and fathers, sisters and brothers, wives and children everywhere are equally devastated at their losses. All ask the same question, and it is the very question we must also keep before us as we are gathered here to do honor to, and pay respect to, those who have died in the service of their country.

I do not like the expression – “gave their lives for their country.” That to me implies some kind of intention to go and not return. Armed conflicts have always relied upon that sense of invulnerability that the young enjoy, to send them with a certain eagerness to play a role in the Army or the Navy or the Air Force. I think, and hope, that all of them have every intention of coming home fit and well, appreciated by their country and with a sense of having furthered the cause of peace. But even among the survivors, it is not always that way.

In my last job in New York I was asked to be on the selection committee to choose a national chaplain to oversee the activities of the Church’s corps of service chaplains – several hundred of them stationed all over the world. The candidates were narrowed down to three, and it was a hard choice as they were all very well qualified. Each candidate told us things we did not know. Things that change and expand the ministry of chaplaincy in terms of scope and in terms of longevity. They all spoke of the very substantial percentage of service men and women who came home with devastating injuries. In times past they would have all died, but now modern field medicine saved their lives, but not their limbs.

Thousands of them suffer brain injuries caused by their heads being banged about in those large and instrument-laden helmets – designed as much to provide tactical information and communications, as they are to protect the head.

We don’t think much about this aspect of the lives and work of those who fight for us, even on days such as Remembrance Day, although we should. Nor do we think deeply about who these men and women are. The life in service is not for every one, no, not at all. If it is for the sons and daughters of the rich and famous at all, it is through the portals of officer school and the privileges of rank.

As far as the rank and file in concerned, the Service life is an option when jobs are scarce and one’s social rank prevents a life in banking or commerce or politics.

Here are a few statistics that I think you will find shocking – a recent study shows that almost 60% of veterans suffered physical abuse as children, and almost 40% suffered sexual abuse. In one country, in 2010, the Army reported more deaths by suicide than deaths in the field.

Over 50% suffer some form of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and almost all have heightened awareness, and reaction to, excessive light and sound.

Much has been written in recent years about how congregations can help returning service people find peace and reconciliation after their field experiences. I don’t believe we have that opportunity but hundreds of congregations do, and are treating this ministry as vital, learning how to avoid clichés and platitudes and how to gently ease these men and women, injured as much psychologically as physically, back into the mainstream of community life.

Military families need support as well. It is hard to even imagine the pressures placed on a family unit as the returning veteran deals with spouse and children who cannot really conceive of the things he or she has so intimately experienced.

The words from Zephaniah may not resonate easily with us. At first one wonders what has possessed the compilers of the lectionary to choose such a reading for today. But I might speculate that they would resonate clearly with someone whose memories are shot with the terrible possibilities of which Zephaniah speaks.

The uncertainty, the apprehension, the sudden percussion, the falling rubble, the dust, the debris, the shattering noise, the blinding incendiary. Thank God most of us will never know it – but every veteran does.

The words of Paul to the Thessalonians may not resonate immediately with us either, but they are actually words of encouragement.

Certainly Paul employs some military imagery but he is really saying that there is an alternative to conflict. This reading is a kind of mirror image to Zephaniah. It shows that there is another way, another ideal, another possibility. We need to hold these peaceable possibilities in mind even as we remember those who carried those ideals into the field of conflict itself.

Last week the Prime Minister entertained the organization that offers support to veterans, at a party at 10 Downing Street. His remarks, aimed as much at the cameras as at those present, were a study in political opportunism. His speech writer had dredged up every cliché possible. Apart from his probably intimate knowledge of the line item in the national budget, it was pretty obvious that he had no real empathy with the work of rehabilitating veterans.

I wish his speechwriter had instead translated the gospel story we’ve listened to this morning into a more meaningful and more sincere message for the cameras. Even when delivered by well groomed and sleek Prime Ministers, the truth can be convincing.

The resources delegated to the servants in the story were in fact immense. The responsibility therefore delegated to them was immense as well. The talent was a huge amount of money, and the risks involved in investing it were huge as well.

Time is a crucial element in the gospel story as well. Jesus is preparing his hearers for the uncertainty of the time element – they were expecting His return to be immediate but he says that is not to be the case. Instead, that information is hidden, and therefore the need for proper preparation and anticipation.

Next, actually possessing the money in the first place is not evidence that the enterprise will succeed. The talents were bestowed because the owner believed his servants already had ability to succeed. The entrusting of the money did not necessarily carry with it the actual ability to succeed.

Then, there is the element of risk, and as we know, one of the servants did not take any risk. He kept his part of the money secure, but he did not use it to achieve anything. He did not do the work that the other two did. His was a passive engagement with the task; theirs was active.

Lastly, the issues of reward and punishment. There are consequences to every decision, every action, every engagement.

The men and women of the armed services are a priceless resource – they are people, they are real, and their value as children of God is immeasurable.

They are given tasks that do not fall into the ideal definition of life. They must take enormous risks, make value judgments and deploy their resources with boldness and with not much time to ponder decisions. There are not many rules as to who succeeds or fails to succeed – but their trajectory has to be forward. They cannot be idle, like the third servant.

All three servants respond to their own view of the Master – two are inspired to please him and to succeed in the goals he has set. The third does not trust the Master and fears his reaction if he should not succeed. It is as if he said to himself “I knew you were unreasonable, and that there was no way to please you, so I decided not even to try”.

This tells us that both conflict and opportunity must be met by people who may or not be qualified. Trained, yes, but temperamentally qualified, not necessarily.

Either way, what we ask of the women and men of the armed forces is not reasonable, yet we expect it of them anyway.

And therein lies the real reason we gather today. Rising to do the work of war is the response to an unreasonable request – and in some cases, demand. Yet veterans did respond, did grasp the higher vision, and did what we have come to call duty

despite the risks.

We remember the ones who could not return. We care for the ones whose injuries prevent their being able to enjoy a full life. And we nurture back to health the ones whose experiences have wounded them in other ways.

And we commend them to God’s loving and healing care, even as we earnestly continue to pray for the peace that they have tried to attain.

Friday, October 28, 2011

Election postponed

After a year of hard work on the part of so many, particularly the committee whose task it was to present nominees to the diocesan convention, that convention has been postponed until November 19 because of a big snowstorm headed our way. What a frustration to everyone concerned! I have planned for a long time to spend a month's vacation with a dear friend in Europe beginning Nov. 10, so it looks like not only will I not be the convention chaplain, I won't even vote!

I arrived in NYC around 4pm to stay at the House of the Redeemer, and had planned to have dinner with Carl Sword, OHC. Looks like dinner and a late train back tonight.

There must be an appropriate scriptural passage for this sort of thing. If it occurs to me, I'll log back in and add it. Something about the best laid plans going a'glay, or however the Scots spell it. They're all good Calvinists steeped in scripture, so even if it isn't in the Book it probably should be.

I arrived in NYC around 4pm to stay at the House of the Redeemer, and had planned to have dinner with Carl Sword, OHC. Looks like dinner and a late train back tonight.

There must be an appropriate scriptural passage for this sort of thing. If it occurs to me, I'll log back in and add it. Something about the best laid plans going a'glay, or however the Scots spell it. They're all good Calvinists steeped in scripture, so even if it isn't in the Book it probably should be.

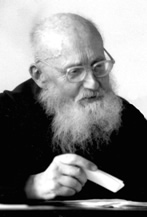

Adalbert de Vogüé OSB

"The Abbey of Pierre qui Vire announces the painful and enigmatic death of P. Adalbert de Vogüé OSB, 86. His body was found 2 km from the monastery after a search of eight days. He probably died Friday, 14 October 2011. The publication of Community and Abbot in the Rule of Saint Benedict (1960) began a distinguished career of research and publication concerning the Rule of Saint Benedict and early monastic literature. He served frequently on the faculty of the Pontifical Athanæum of Saint Anselm in Rome before taking up the hermit's life in 1974 near his monastery. The monks will celebrate the Mass of Christian Burial, Wednesday, 26 October, 11 a.m. Donne-lui, Seigneur, le repos éternel."

With these words the Abbey of La Pierre qui Vire announced the death of the greatest scholar of monastic texts in the world. Adalbert de Vogüé was born in 1924 in Paris to a wealthy and aristocratic family. His father was son of the Marquis de Vogüé and the princess Louise-Marie d'Arenberg, and was a principal officer in the Crédit Lyonnais. His mother was from an equally distinguished and even more prosperous family. Adalbert joined the Abbey of La Pierre qui Vire in 1944. His parents both decided to follow him into the cloister, and amid great publicity in 1955 his father entered La Pierre qui Vire and his mother entered Abbaye Saint-Louis-du-Temple de Vauhallan at Limon.

In 1960 de Vogüé published his first major book, translated into English as Community and Abbot in the Rule of St. Benedict. His scholarly work concentrated on the Benedictine monastic tradition. His editions and commentaries of the Rule and of Gregory the Great's Dialogues, Book II of which contains virtually all we know about Benedict as a person, are standard. He published hundreds of other books and articles, but his crowning work is the 12 volume Histoire littéraire du mouvement monastique dans l'antiquité, a magisterial survey of every written monastic source in Latin from the beginnings to the Carolingian Benedict of Aniane.

De Vogüé was a complicated man. He received a fine education in Paris and Rome and taught many terms at San Anselmo, the Benedictine college in Rome. He lectured widely and participated in the intellectual and academic life of his patristic and monastic specialties. He also traveled. I had the great honor of meeting him when he was a guest at the Monastery of St. Paul in the Desert in Palm Desert in the 80's. He was also devoted to the most austere forms of monastic life, and spent many years living in semi-seclusion at a hermitage near his monastery. He wrote occasionally on the ascetic life, of which he was a powerful proponent, and not of the school of amelioration for the purposes of making such a life relevant to modern people. His was the full-throated cry of the completely committed, and his passion can best be seen, perhaps, in his little book To Love Fasting.

He was just as full-throated in his interactions with scholars with whom he disagreed. Not a few revisionists of monastic history experienced his sharp disagreements. And with all that, De Vogüé was the greatest scholar in the Benedictine world for fifty years. It is not too much to say that he is in great part responsible for the brilliant flowering of interest in Benedictine monasticism, having laid a solid foundation for the rest of us to build on.

I can't help thinking both how fitting and how ironic his death was -- lost to others in the forests several kilometers from the monastery, his death hidden from the world he both embraced and fled.

Tuesday, October 25, 2011

Electing a Bishop

On Saturday, Oct. 29, the Diocese of New York will gather in convention to elect a coadjutor bishop. Bishop Sisk has asked me to be the the Chaplain to the Convention. Seven have been nominated, five officially and two by petition. One has withdrawn. The slate was announced at the end of August, and on Tuesday afternoon, Oct. 11, a process of interviewing the candidates began at Christ Church, Poughkeepsie, and continued through the week in six or so other venues.

It was an interesting process. It helped clarify my own thoughts about the candidates to some extent. It is helpful to meet and listen to and observe people in the flesh as well as in their carefully prepared statements and videos and other self-presentations. But more importantly, it helped me to solidify my own thoughts about what the next Bishop of New York might be and do. I share those thoughts here, with the understanding that as I write about them, none of them are criticisms of our current Bishop. No one person can have every gift, and the gifts for which a bishop is elected at one point may not be the same needed a decade or more down the road.

So what do I think is most important in our next bishop?

First, I think that the Bishop should be a clear voice proclaiming Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior. That sounds trite, I know, so let me explain. I believe the Church exists to call people to a new reality. The scriptural name for that reality is the Kingdom of God. It goes by other names, even in Scripture: the Kingdom of Heaven in Matthew, everlasting life in John, salvation in its many forms in Paul. This is not a simple matter, because it involves scriptural interpretation and sound, contemporary theology as well as participation in the modes of understanding with which our culture describes reality. But that proclamation is at core quite clear: There is a new reality to which the Church calls the world, and that reality has its point of origin and its summation in the person of Jesus Christ. So our new bishop needs to be someone who can proclaim that reality publicly, persuasively, consistently and effectively, not only from the pulpit, but in the many different roles he or she will be called to fill institutionally and in the wider community. The Bishop should be one who makes clear that the Church is impelled by this new reality to begin working for it here and now, and that our many works for the poor, for the education of the young and for social advancement flow from this one source: We believe the Kingdom can begin here and now.

Second, I think that the Bishop needs to love, effectively represent and skillfully promote the kind of Christianity the Episcopal Church stands for. We are catholic and we are reformed. Which is to say, we stand for the full practice of the sacramental, liturgical, theological and ecclesial reality of the historic western Church, and we also stand for the freedom of conscience of each believing person within the fellowship of Christ, and all that follows from that in the full participation of all members in the Church's life, witness and governance. The Bishop needs to be a person who can lead us into the challenges to our form of Christianity in the contemporary moment. These are clear to everyone, but the way forward is not so clear. The Bishop needs to be a skillful institutional leader, one who can envision and implement appropriate new or changed forms of congregational and diocesan ministry. The challenges we face include an aggressively materialist culture which is in many ways opposed to the Christian message, a psycho-social environment which does not value Christian belief commitment very highly, and a financial environment in which there is less money for church structures. The Bishop should be a person who faces our future with optimism because he or she believes in the Anglican way of being Christian, believes that our way is essential for the completeness of the universal Church, and believes that the Anglican way is given by God as one proclamation of the Gospel in our society.

Third, I think that the Bishop needs to be a person who loves holiness: a person of personal prayer and reflection breaking into attitudes of generosity and good discernment toward others, of course, but also a person who wants to promote holiness though the Church. The Episcopal Church has chosen the path of radical inclusiveness, not just in areas of sexuality and gender, but in many other areas as well. How are people transformed by their life in Christ within the Episcopal fellowship? How can the Church build up the Kingdom of God by including people who have been excluded, from the Church altogether in some cases, or from our church in particular in others, as they are drawn into fellowship with those who are already members? The Bishop should be a person who in his or her own personal life is known to be living the life of the Kingdom, but also a person who can call everyone to the challenging work of refashioning their lives, no matter when they entered the vineyard (see Matthew 20:1-16). This is all the more urgent in a time when the traditional educational and economic prospects for young people no longer hold their old promise, when the moral and social conventions of the past, built on socially agreed foundations, no longer hold as firmly as they once did. People need to look to us as a church which calls its members with some success to the struggle to be what God intends us to be, which is not and should not be easy. Thoughtful people find themselves drawn to effective disciplines of holiness. The Church, led by its bishop, should be a place where they can find them.

This is a lot. I am pretty sure no one person has all the qualities needed. But whoever we elect should have these as ideals, as goals, for the episcopal ministry. It is trite to say that the Church is at a turning point. The Church has always been at a turning point, because to be alive in any present moment is to have to choose, to turn toward what is coming. Nevertheless, I believe this is such a moment. I pray that our new Bishop will be a person who can represent the values we carry with us from our tradition and do so with cheerful confidence that the challenges that face us are opportunities, and energize us in the Spirit.

It was an interesting process. It helped clarify my own thoughts about the candidates to some extent. It is helpful to meet and listen to and observe people in the flesh as well as in their carefully prepared statements and videos and other self-presentations. But more importantly, it helped me to solidify my own thoughts about what the next Bishop of New York might be and do. I share those thoughts here, with the understanding that as I write about them, none of them are criticisms of our current Bishop. No one person can have every gift, and the gifts for which a bishop is elected at one point may not be the same needed a decade or more down the road.

So what do I think is most important in our next bishop?

First, I think that the Bishop should be a clear voice proclaiming Jesus Christ as Lord and Savior. That sounds trite, I know, so let me explain. I believe the Church exists to call people to a new reality. The scriptural name for that reality is the Kingdom of God. It goes by other names, even in Scripture: the Kingdom of Heaven in Matthew, everlasting life in John, salvation in its many forms in Paul. This is not a simple matter, because it involves scriptural interpretation and sound, contemporary theology as well as participation in the modes of understanding with which our culture describes reality. But that proclamation is at core quite clear: There is a new reality to which the Church calls the world, and that reality has its point of origin and its summation in the person of Jesus Christ. So our new bishop needs to be someone who can proclaim that reality publicly, persuasively, consistently and effectively, not only from the pulpit, but in the many different roles he or she will be called to fill institutionally and in the wider community. The Bishop should be one who makes clear that the Church is impelled by this new reality to begin working for it here and now, and that our many works for the poor, for the education of the young and for social advancement flow from this one source: We believe the Kingdom can begin here and now.

Second, I think that the Bishop needs to love, effectively represent and skillfully promote the kind of Christianity the Episcopal Church stands for. We are catholic and we are reformed. Which is to say, we stand for the full practice of the sacramental, liturgical, theological and ecclesial reality of the historic western Church, and we also stand for the freedom of conscience of each believing person within the fellowship of Christ, and all that follows from that in the full participation of all members in the Church's life, witness and governance. The Bishop needs to be a person who can lead us into the challenges to our form of Christianity in the contemporary moment. These are clear to everyone, but the way forward is not so clear. The Bishop needs to be a skillful institutional leader, one who can envision and implement appropriate new or changed forms of congregational and diocesan ministry. The challenges we face include an aggressively materialist culture which is in many ways opposed to the Christian message, a psycho-social environment which does not value Christian belief commitment very highly, and a financial environment in which there is less money for church structures. The Bishop should be a person who faces our future with optimism because he or she believes in the Anglican way of being Christian, believes that our way is essential for the completeness of the universal Church, and believes that the Anglican way is given by God as one proclamation of the Gospel in our society.

Third, I think that the Bishop needs to be a person who loves holiness: a person of personal prayer and reflection breaking into attitudes of generosity and good discernment toward others, of course, but also a person who wants to promote holiness though the Church. The Episcopal Church has chosen the path of radical inclusiveness, not just in areas of sexuality and gender, but in many other areas as well. How are people transformed by their life in Christ within the Episcopal fellowship? How can the Church build up the Kingdom of God by including people who have been excluded, from the Church altogether in some cases, or from our church in particular in others, as they are drawn into fellowship with those who are already members? The Bishop should be a person who in his or her own personal life is known to be living the life of the Kingdom, but also a person who can call everyone to the challenging work of refashioning their lives, no matter when they entered the vineyard (see Matthew 20:1-16). This is all the more urgent in a time when the traditional educational and economic prospects for young people no longer hold their old promise, when the moral and social conventions of the past, built on socially agreed foundations, no longer hold as firmly as they once did. People need to look to us as a church which calls its members with some success to the struggle to be what God intends us to be, which is not and should not be easy. Thoughtful people find themselves drawn to effective disciplines of holiness. The Church, led by its bishop, should be a place where they can find them.

This is a lot. I am pretty sure no one person has all the qualities needed. But whoever we elect should have these as ideals, as goals, for the episcopal ministry. It is trite to say that the Church is at a turning point. The Church has always been at a turning point, because to be alive in any present moment is to have to choose, to turn toward what is coming. Nevertheless, I believe this is such a moment. I pray that our new Bishop will be a person who can represent the values we carry with us from our tradition and do so with cheerful confidence that the challenges that face us are opportunities, and energize us in the Spirit.

Thursday, October 20, 2011

The Joy of Old Friends

Practically the only people I know in Austin are Bill and Molly Bennett. We met years ago at CDSP, where Bill was in charge (I think) of development in 1976 when I started studying for my M.Div. there. I remember well doing my work/study thing as a janitor and being told by Bill how important it was to empty the wastepaper baskets. As it surely is. At any rate, we became friends then.

Bill went on in the mid-80's to become the Provost at the Episcopal Seminary of the Southwest in Austin, working together with Durstan MacDonald as Dean. It was a good partnership and the seminary flourished under their leadership. Eleven years later or so Bill became the rector of St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Austin, and retired some years ago. Molly worked for years as a Director of Christian Education in Austin Episcopal churches and was responsible for establishing the certification program in Christian Ed at ETS-SW. Both have had distinguished careers.

I had e-mailed in advance, and when I got to Austin I called them up and plans were made. We went for dinner last night at a wonderful place called the Eastside Cafe. The food was delicious. I had mushroom crepes and squash and we all had a scrumptious cherry cobbler for dessert. But of course the nicest part was the conversation. We talked and talked about old friends and the Church, and then they took me on driving tour of downtown Austin. I was a bit taken aback when Bill told me about the Temple of the Holy Spirit which had either six or nine (I'm not sure I remember the number correctly) gatherings a year when more than 100,000 people attend worship. Then I looked up and lo and behold, the U. of Texas stadium. I told Bill I was acquainted with that form of worship, having attended Michigan State in The Good Old Days when Duffy Dougherty was coach.

What a wonderful thing old friends are!

Bill went on in the mid-80's to become the Provost at the Episcopal Seminary of the Southwest in Austin, working together with Durstan MacDonald as Dean. It was a good partnership and the seminary flourished under their leadership. Eleven years later or so Bill became the rector of St. Mark's Episcopal Church in Austin, and retired some years ago. Molly worked for years as a Director of Christian Education in Austin Episcopal churches and was responsible for establishing the certification program in Christian Ed at ETS-SW. Both have had distinguished careers.

I had e-mailed in advance, and when I got to Austin I called them up and plans were made. We went for dinner last night at a wonderful place called the Eastside Cafe. The food was delicious. I had mushroom crepes and squash and we all had a scrumptious cherry cobbler for dessert. But of course the nicest part was the conversation. We talked and talked about old friends and the Church, and then they took me on driving tour of downtown Austin. I was a bit taken aback when Bill told me about the Temple of the Holy Spirit which had either six or nine (I'm not sure I remember the number correctly) gatherings a year when more than 100,000 people attend worship. Then I looked up and lo and behold, the U. of Texas stadium. I told Bill I was acquainted with that form of worship, having attended Michigan State in The Good Old Days when Duffy Dougherty was coach.

What a wonderful thing old friends are!

Monday, October 17, 2011

At the Archives

I'm in Austin, TX, until Friday to work on OHC's archival holdings on deposit at the national Episcopal Church archives, which are located on the campus of The Seminary of the Southwest (SSW) (which used to be prefixed with Episcopal Theological, as in ETS-SW). There was no room in the inn there, so I am staying at the Austin Presbyterian Seminary, in very nice digs called the Presidential Condo. It's a one-bedroom condo on the third floor of a married student housing building north of the seminary, very close to SSW and the Archives.

The flight down took me from Stewart-Newburgh to Detroit and Atlanta and then on to Austin. No problems at all. You would never know Detroit is collapsing from its airport, which is quite spiffy, as is Atlanta. The less said about Stewart the better, but the planes leave on time and occasionally arrive on time as well. The TSA people at Newburgh are not at all like the caricatures of those folks. They were pleasant, efficient and friendly. But we still had to take our shoes off.

The Order has had the bulk of our archives in Austin since 1976, and it is a lot of stuff. I'm mostly confirming and improving the descriptions of our holdings and will do a bit of scanning as well.

Austin being in Texas and all, I'm going to go out for a steak tonight. Last night I had a pretty good burger at a little place just down the street, but tonight I'm up for the real thing. People have recommended the Austin Land and Cattle Company (not to be confused, I was urged, with the Texas Land and Cattle Company). Apparently the Austin version has the more authentic down home Austin feel to it, and perhaps more reasonable prices as well.

I visited Austin and the Archives in the mid-80s when I did research there for the history of OHC. The Archives then was run by Nell Bellamy, of very blessed memory, a great woman, a great Christian and something of a saint, at least in my book. Today I had the opportunity for a good conversation with her successor, Mark Duffy, and he is, as they say, Worthy.

Austin is pretty much as I remember it, at least this part of it. I was struck then and continue to be by the casual approach to sidewalks and curbs here. Not at all like southern California, where they approach fetishism. There was some rain a couple of weekends ago, so things are not totally parched, but the drought is still very much on.

The flight down took me from Stewart-Newburgh to Detroit and Atlanta and then on to Austin. No problems at all. You would never know Detroit is collapsing from its airport, which is quite spiffy, as is Atlanta. The less said about Stewart the better, but the planes leave on time and occasionally arrive on time as well. The TSA people at Newburgh are not at all like the caricatures of those folks. They were pleasant, efficient and friendly. But we still had to take our shoes off.

The Order has had the bulk of our archives in Austin since 1976, and it is a lot of stuff. I'm mostly confirming and improving the descriptions of our holdings and will do a bit of scanning as well.

Austin being in Texas and all, I'm going to go out for a steak tonight. Last night I had a pretty good burger at a little place just down the street, but tonight I'm up for the real thing. People have recommended the Austin Land and Cattle Company (not to be confused, I was urged, with the Texas Land and Cattle Company). Apparently the Austin version has the more authentic down home Austin feel to it, and perhaps more reasonable prices as well.

I visited Austin and the Archives in the mid-80s when I did research there for the history of OHC. The Archives then was run by Nell Bellamy, of very blessed memory, a great woman, a great Christian and something of a saint, at least in my book. Today I had the opportunity for a good conversation with her successor, Mark Duffy, and he is, as they say, Worthy.

Austin is pretty much as I remember it, at least this part of it. I was struck then and continue to be by the casual approach to sidewalks and curbs here. Not at all like southern California, where they approach fetishism. There was some rain a couple of weekends ago, so things are not totally parched, but the drought is still very much on.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

One of life's little signposts

Well, I suppose it had to happen sometime. I'll be turning 65 in December, so I made my appointment to apply for Medicare and had the interview today. I know you can do it online, but somehow I felt I'd rather talk to a human being about this little milestone in the journey. So I got myself up to the Social Security office in Kingston, which is on the second floor of a nice but somehow sterile and forlorn office building out in Lake Katrine, north of the big box shopping district, near nothing at all.

The man who interviewed me was very nice, very helpful. I was glad I had taken along all the documents. The birth certificate in particular. He tried to get me to retire on the spot, but I think I'll wait a while. The full retirement for my age cohort is 66, and the monthly haul increases a bit each month you wait to retire after that.

Coming down the stairs I could have sworn my knees were complaining.

The man who interviewed me was very nice, very helpful. I was glad I had taken along all the documents. The birth certificate in particular. He tried to get me to retire on the spot, but I think I'll wait a while. The full retirement for my age cohort is 66, and the monthly haul increases a bit each month you wait to retire after that.

Coming down the stairs I could have sworn my knees were complaining.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

The marriage feast

After more than a month taking services at St. George's, Newburgh, I preached at Holy Cross Monastery this morning. St. George's prefers an informal preaching style, but this morning's offering was written. It is posted on the sermon blog for Holy Cross Monastery and can be reached there.

Monday, September 5, 2011

Conflict Resolution for Labor Day

Preached at The Church of the Incarnation, New York City, September 4, 2011

Ezekiel 33:7-11

Romans 13:8-14

Matthew 18:15-20

Our lessons this morning all in one way or another refer to the resolution of conflict. How interesting that they should occur on the weekend of Labor Day.

The labor movement in this country began as a serious force in the 1880's. Founded in 1869, the first major American labor organization, the Knights of Labor, had only 28,000 members in 1880, and grew to an astonishing membership of 700,000 by 1886, just six years! Something big was going on! The founder of the Order of the Holy Cross, James Huntington, joined the Knights here in New York City and quickly became a national figure supporting the rights of working people, helping to bring their concerns into the heart of the Episcopal Church. The Knights of Labor could not maintain that level and its membership soon fell back, but its rapid growth showed the industrial and political community that organized labor was a force to reckoned with. The Knights of Labor paved the way for an industrial order which eventually came, through struggle, to recognize the rights and dignity of working people. That struggle takes different forms in our own age, perhaps, but it is perpetually necessary, even in times when the creation of work through capital itself seems endangered. And conflict was part of that struggle.

Our three lessons this morning all deal with conflict in one way or another. The prophet Ezekiel is commissioned by the Lord to warn the wicked. But Ezekiel seems not to want to follow through. The Lord has to tell him that if he does not warn them and disaster comes, the blood will be on his hands. So this conflict is dealt with by telling the truth regardless of its consequences to the teller. If people are not warned, they will not change. If they are warned, they may not change anyway, but at least they have had the option presented to them. So, the prophet says, Change while you have the chance.

St. Paul takes another tack. We know what we should and should not do. The Law tells us – adultery, murder, theft, greed are going to cause conflict for sure. Paul wants us to understand how urgent our lives are. We may think there is all the time in the world to resolve things. We may excuse ourselves because keeping the law is complicated. But actually, Paul says, in some of the most inspired words of scripture, Wake up. The time is now. Start living without building up toxic debts to each other. “Love one another; for the one who loves another has fulfilled the law.” If Ezekiel recommends truth telling, Paul recommends living as though the other person is as important, and as worthy of love, as we are.

The passage from St. Matthew’s gospel comes as a surprise in this context. When conflicts arise in the Church, as they always have, and I suspect they always will, one might expect Jesus to tell the believers to turn the other cheek, as he does in another context, the context of an individual choice. But this is a group situation which requires a different approach. So Jesus recommends a conflict resolution process. First talk to the person you have your problem with. If that doesn’t work, bring in another person or two. If that doesn’t work, take it to the congregation. And if that doesn’t work, invite the person to leave. You can almost imagine Jesus writing this out in large letters on big pieces of paper and taping them to the wall during a conference called something like “Conflict Resolution in the Church”. A morning session at a retreat center just outside of Capernaum, by scenic Lake Galilee, perhaps. Jesus the Conference Facilitator. Joking aside, conflict happens, and it clearly happened in the early church. So procedural. So sensible. So sane. So boring.

Except, the ways conflicts were resolved in Jesus’ time were often quite violent. Just look at the 18th chapter of Matthew, from which this passage comes. Earlier in the chapter, it is said, "If your hand or your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away; it is better for you to enter life maimed or lame than to have two hands or two feet and to be thrown into the eternal fire. And if your eye causes you to stumble, tear it out and throw it away; it is better for you to enter life with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into the hell of fire.” And after our passage, a story about forgiving debts, which ends: “And in anger his lord handed him over to be tortured until he would pay his entire debt. So my heavenly Father will also do to every one of you, if you do not forgive your brother or sister from your heart." Jesus was using these images because they are familiar – all too familiar – to his hearers. If this is the way people deal with themselves and with members of their own extended households, how will they deal with outsiders?

And that is the point of this passage, I think. Jesus wants the church to be different, to start something new. Jesus is saying to the church, Even though you come from different families, different towns, different languages and cultures and nations, you are not outsiders to each other. You have a responsibility to listen to each other. You are still bound to come to a just decision, and when you do, the Father will support you, But this must not be done with violence in any case, as is the way of the world.

Jesus is preaching the Kingdom of Heaven here. The world, God’s world, is enveloped in violence, violence which we commit upon ourselves and upon each other, unthinkingly, almost unconsciously, because that is the way of things. And perhaps it can’t be avoided, although I do think that the Middle Eastern love of rhetorical hyperbole should be considered as an interpretive tool for scripture when we are tempted to follow its advice and pluck out eyes or torture each other as means to spiritual progress. But the believing fellowship, the church, is the place which is expressly dedicated to beginning to live in the Kingdom of Heaven, And so here, Jesus calls his followers to another way, a way which is contrary to the way their world operates, to a counter-culture. It is not acceptance of what is wrong. It does not facilitate the offender. But it gives the offender three distinct forums to repent, not unlike Ezekiel’s prophetic call to tell the truth. And if that does not work, the punishment meted out is not eye gouging or hand amputation or torture. It is simple exclusion. If you cannot come to terms with the honest judgment of those who love you as a brother or sister in the Lord, then you don’t belong in the fellowship. Perhaps the Kingdom of Heaven is not for you.

How different from the organized violence of the Roman state. How different from the rhetorical violence of the thought world of Jesus’ hearers, How different from a world in which you have the duty to practice violence on those outside your kinship group at the slightest pretext, and how different from a world in which the enforcement of discipline on those inside the family can call for torture. Jesus wants to transform the conflict of the world, and he wants the church to lead the way.

The history of labor and industrial relations in this country is a history filled with violence. But it is also a history of learning to listen, sitting down one to one, in small groups, and in assemblies if need be. It is a history of learning to hear each other, and of learning that each needs the other.